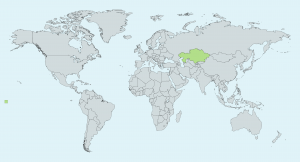

Following the collapse of Soviet farming systems in Central Asia, substantive declines in the productivity of agriculture were observed throughout central Asia. In recent years, effective intensive agricultural systems, particularly pastoralism, are returning once more. However, the consequences for the sustainable use of these grasslands, and impacts on livelihoods among the region’s rural poor are hard to predict. This expedition, funded by BCAI, aims to measure the impacts of intensification on agricultural productivity and sustainability in central Kazakhstan and to evaluate farmer attitudes to new sustainable approaches to agricultural production. The following blogs were written by Hannah Rose during an expedition to Kazakhstan.

Hannah Rose

Ghost towns on the Kazakh steppe look as though they are centuries old, but it is an illusion. They have been sandblasted relentlessly by the force of the steppe since they were abandoned, less than 40 years ago, after the breakdown of the Soviet Union. This is one area on earth that people have largely failed to tame, but as the human population increases the country’s agricultural systems are rapidly developing and focus is turning to the steppe once again. At the same time, farmers must adapt to recent changes in climate – drier summers limit crop production and water availability, and changing patterns of snowfall and snowmelt threaten the lives of livestock. I am about to embark on a remote expedition to find out more about Kazakh agriculture and how farmers are responding to their changing landscape.

Since 2000, approximately 5,000,000 additional hectares of land have been sown for cropping, and approximately 2,000,000 each additional sheep, cattle and horses are kept in Kazakhstan. This increase in livestock productivity is largely driven by smallholder farmers, who rely on livestock for up to a fifth of their family’s food. However, climate change has been felt disproportionately in Central Asia, threatening food security. National Geographic recently reported that over half a million animals failed to survive the winter in neighbouring Mongolia due to a combination of lethal winter conditions and poor summer crop growth, so I’m anxious to see how the Kazakhs fared.

I’m told that in the Ural region in Western Kazakhstan, wheat production, livestock and wildlife exist in close contact and that this is the best place to start my research. I’m set to fly to Astana tomorrow to join colleagues from the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (ACBK) on the three-day, 2,000km journey to the far west. With the help of ACBK and Bristol PhD student Munib Khanyari, I will interview farmers spread out over an area the size of England, skirting along the Russian border and the Caspian Sea. I’ll spend my evening’s wild camping off-grid under the stars for 2-3 weeks. There will be no fresh water, no toilets and no internet – the team and I have to carry everything we need in order to survive the duration. Wish me luck!